Researchers at Vitalité Health Network imagine a health-care system where patients are screened early for a disorder or disease they inherited from their parents, and mothers know exactly what health problems they could pass down to their children before ever getting pregnant.

But first, medical teams need to know which genetic variants are common in specific regions of New Brunswick. Luckily, we are built of microscopic indicators that researchers in Moncton are studying so they can figure that out.

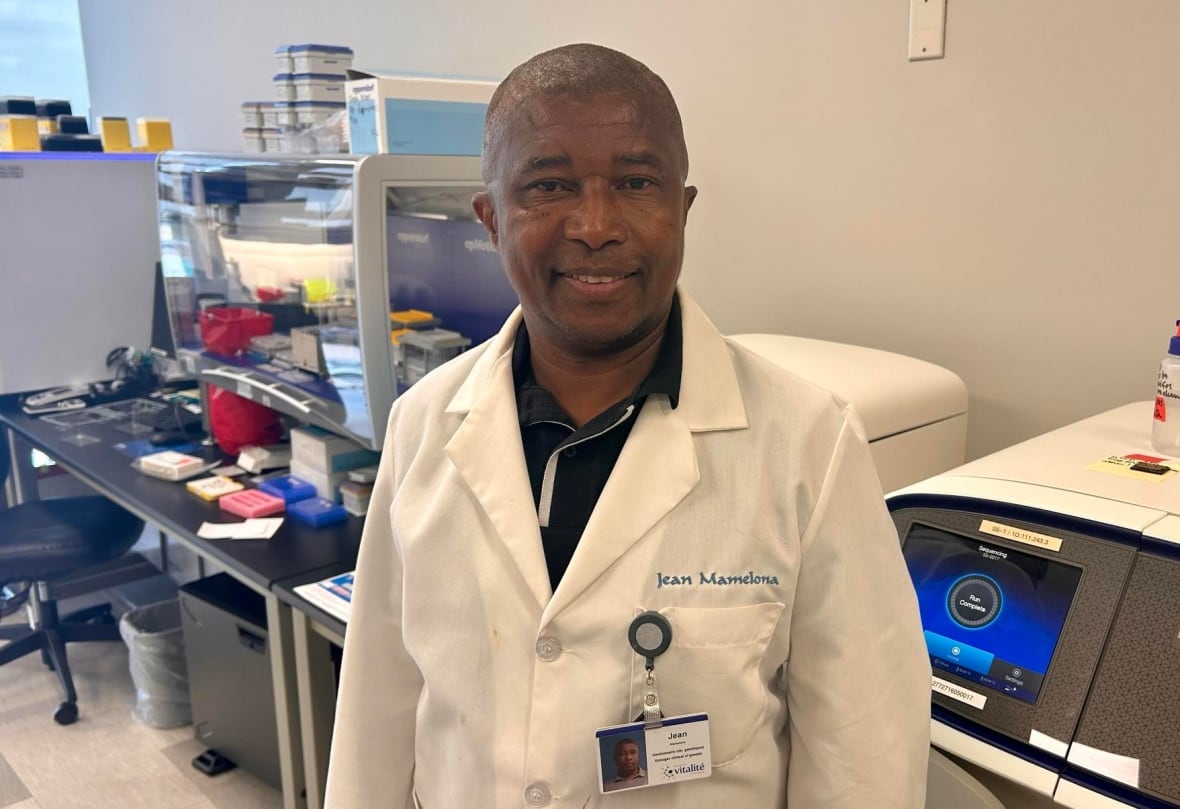

“We have thousands of genes,” Jean Mamelona, who runs the provincial program of medical genetics, said. “We are going, specifically, to analyze the genes to see if there is a defect or … a default on the gene.”

Mamelona and his research team at the Dr. Georges-L.-Dumont Hospital are touring the province to map people’s genes to build the first database of its kind for each of the seven health zones in the province.

Genes provide a wealth of information about the body. But this research is focused on finding defects, otherwise known as variances or mutations. These can cause genetic disorders.

The hope is that medical teams will use that information to screen people earlier for conditions such as sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis and Huntington’s, among others.

It could also be invaluable to inform more precise neonatal screening, Mamelona said.

“We can plan precision medicine for the area,” he said.

The project, which began in 2018 and is partly funded by Research N.B., is expected to be complete once 60 people in each of the seven health zones have been tested by the end of 2027.

What results among Acadians are telling us so far

Teams have been testing 60 participants in each health zone who can provide medical information and a swab of DNA to be tested.

So far, the team has tested people near Moncton, on the Acadian Peninsula, and in Restigouche and Madawaska.

Researchers in Moncton are studying 60 people in each of the seven health zones in New Brunswick to find common variants in their genes. The hope is that medical teams will be able to use the information to screen patients sooner for inherited diseases and disorders.

Results from some areas, such as the Acadian Peninsula and northwest regions, have not yet been released to the public.

The results from Zone 1, in the southeast, show that Acadians who were tested have similar genetic variants that are likely being passed down from generation to generation.

“We have seen that there are some variants that are really more frequent, compared to Caucasian populations elsewhere around the globe,” Mamelona said.

Forty-three of the 60 participants in the southeast, or 71 per cent of them, were found to be carrying at least one variant. One of the variants was detected in 11 individuals.

For privacy reasons, the researchers do not disclose the specific diseases that each of the variants they found could be linked to.

To historian and Acadian genealogist Denis Savard, the results are no surprise.

He said the similarities in Acadian genes are likely caused by a common thing that happens among smaller ancestral groups.

“It’s what we call a bottleneck effect,” Savard said.

“[It’s] where only a few families, relatively speaking, start off the population, so there’s a limited number of genes to start off even though there’s always people coming in and adding to the population.”

Acadians actually experienced the bottleneck effect twice, Savard said.

It happened once when a limited number of mostly French settlers came to New Brunswick and Nova Scotia in the 1600s. The same thing happened again after Acadians were expelled from the region in 1755, and an even smaller number of them returned to rebuild communities.

“If you look at Restigouche, it’s pretty much the same families for over 150 years, same for Memramcook area,” Savard said.

To the research team, Acadians are a strong example of why the medical community could benefit from more in-depth genetic testing, given that early results point to largely homogeneous genetic variances.

In other words, Mamelona said, if there is a higher prevalence of carriers for the same genetic variants, and we can confirm them across the province, we can screen new generations for them.

Researchers are now trying to recruit in the Miramichi area as they turn their focus to areas of English descent. Saint John and Fredericton are next on the list.

Participants must be at least 19 years old, be covered by medicare, not be expecting a child and have two grandparents who were born in that specific area to qualify for the study.